View from Batman's Hill looking westward, from an original sketch taken in 1836 or beginning of 1837.

Robert Russell, surveyor, 1884. Courtesy of the State Library Victoria Collection. H24527

'Original Flagstaff, 4th September, 1841'

Georgiana McCrae (1804 – 1890) McCrae Homestead Collection, National Trust of Australia (Victoria).

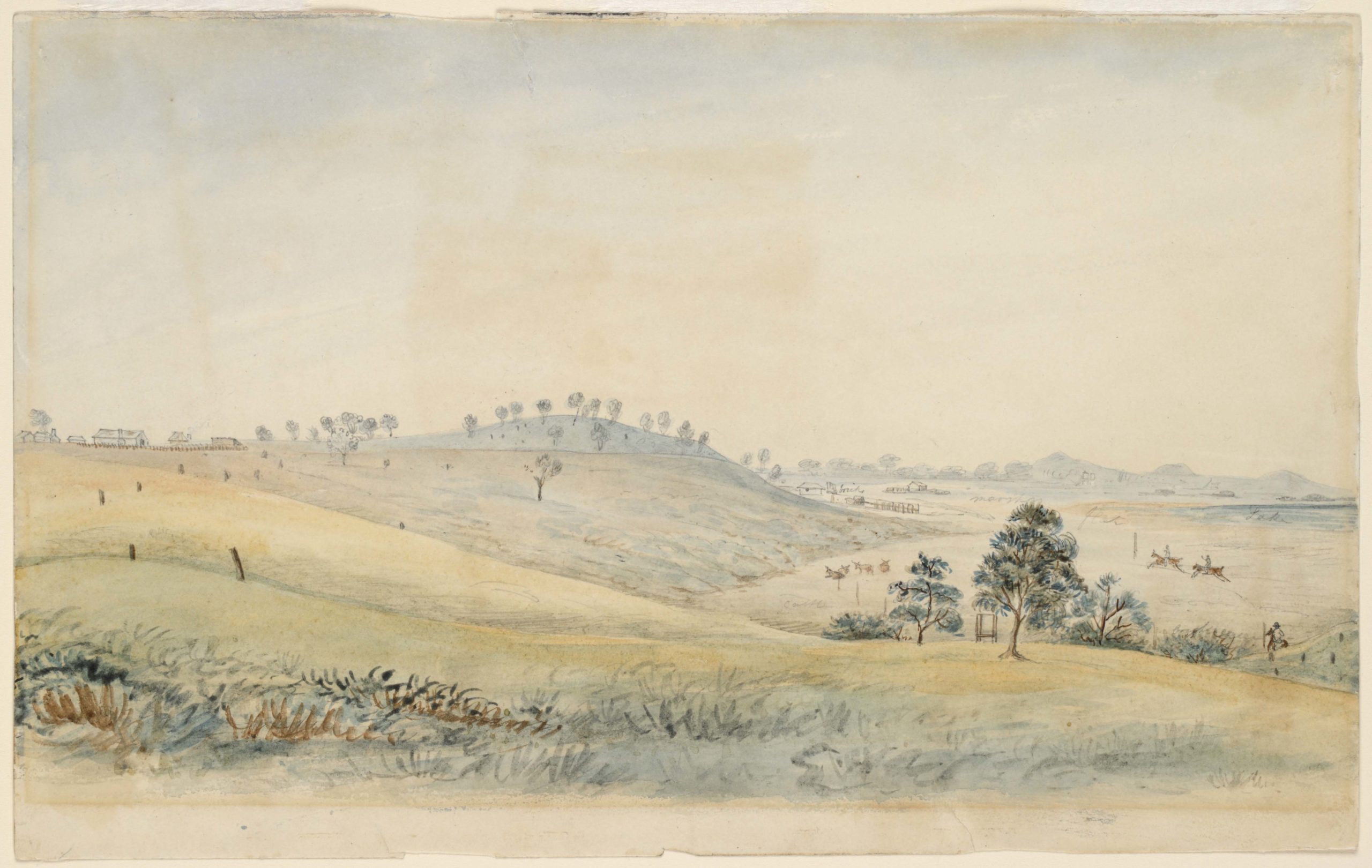

Melbourne, Port Phillip, Racecourse and Survey Office, 1840.

Robert Hoddle. The sketch was made looking east, with the survey office at the top of the hill on the far right, and a sail from a ship in the Yarra to the east. The swamp is centre right. Courtesy of the State Library Victoria Collection. H259.

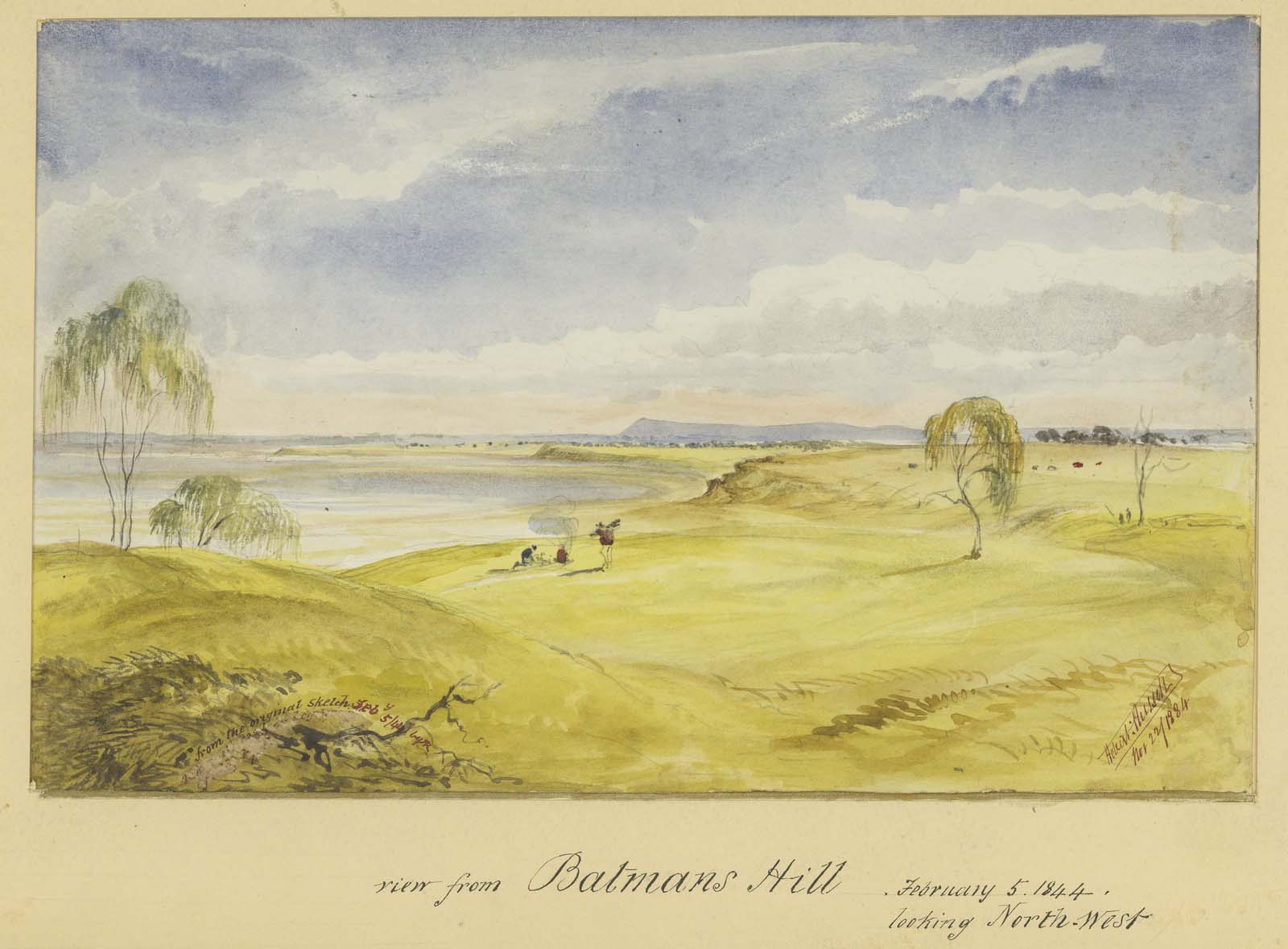

View from Batman's Hill February 5 1844 looking North West

Robert Russell, 1884. Courtesy of the State Library Victoria Collection. H24487.

In the 1830s and 1840s the view of the lagoon from Batman’s and Flagstaff Hills was captured in watercolour. These four landscapes were painted by Robert Russell, surveyor, Robert Hoddle, surveyor, and Georgiana McCrae, artist. Georgiana’s son, George Gordon McCrae, in 1911 provided his recollections of the lagoon to the Historical Society of Victoria, included below.

A report to Fawkner, Monday, August 24th, 1835

By Captain John Lancey

Your lordship has been fortunate in the lot I chose for you. A more delightful spot, I think, cannot be. Beautiful grass, a pleasant prospect, a fine fresh-water river, and the vessel laying alongside the bank discharging at a musket-shot distance from a pleasant hill* where I intend to put your house. The garden will trend to the south by the east side of this hill, at its foot, towards the river, from which it can be easily watered. The west side of the hill is a beautiful prospect. A salt lagoon and piece of marsh will make a beautiful meadow and bounded on the south by the river. This hill is composed of a rich, black soil, thinly wooded with honeysuckle and she-oak. Good grass, a quantity of herbage that I cannot name more than three, viz., parsley of good flavour, peppermint, as good as any I ever tasted, and geraniums in abundance. Indeed, it is almost a task to describe the pleasantness of the situation, as well as its localities for goodness.

*This was evidently the spot later known as Batman’s Hill.

Victorian Historical Magazine, 1928 Issue: 47 Volume: 12, p114.

Melbourne and New Town, Port Phillip.

By Thomas McCombie

To the left of the town, but so close that it all but forms a part of it, is Batman’s Hill a spot of singular beauty. It is a small green hill of conical shape, and the object which generally strikes the eye of a stranger when entering the town. The river Yarra washes its base on one side as it sweeps onward towards the bay. The ascent is rather precipitous on the side which is towards the river but opposite to where we stand it falls gradually away by a gentle slope until it reaches the open plain beyond. The spot has a verdant look the grass delicate and green clumps of trees of fairest hues spread here and there in wild and irregular beauty. How inviting it looks from where we stand, and many an English Peer would give a third of his princely fortune for that spot to adorn his park. It is, in a word, a pure gem of nature which gold could not buy, nor art imitate.

A little farther on is the commencement of a long strip of wet land which beginning at the bank of the river runs parallel with Batman’s Hill and extends far beyond where we are standing. This extensive swamp would deteriorate very much from the perfect beauty of the landscape, were it not that the swamp is nearly always covered with water which gives it all the appearance of a fine lake. The sun sets behind this sheet of water, and, as he radiates in parting splendour from behind that cloudy film, casts a purple canopy upon the water so tenderly beautiful as to subdue the most worldly heart.

“Oh, to see it at sunset when warm o’er the lake,

His splendour at parting a summer eve throws;

Like a bride full of blushes when she lingers to take

One last look of her mirror at night ere she goes”.

Beyond the swamp the Willoughby [ie, Werribee] Plains commence. These extensive plains are somewhat similar to Batman’s Hill, having a sprinkling of trees scattered here and there in groups after the manner of a gentleman’s park in England. The country however is irregular, presenting at times a long succession of green mounds. These will again disappear and the country change its aspect. Instead of the mounds the eye now rests upon extensive undulating flats but with less timber. Beyond the Willoughby [Werribee] but far, far away, so as at times to be indistinct, rise a lofty range of mountains which, beginning near Geelong, a township upon the bay run hundreds of miles into the interior of the country.

Simmonds’s Colonial Magazine and Foreign Miscellany, Volume 7, pp 65 and 66, VOL VII NO 25 JANUARY 1846

Some Recollections of Melbourne in the “Forties”.

By Geo. Gordon McCrae

Nearly all the country to south, north, and west of us was at this period in a state of nature, with just a few cottages dotted over it here and there. On our side of Batman’s Hill (then a beautiful green knoll thickly covered with round-headed she-oaks) stood the white tents of a detachment of the 26th Regiment, producing a very pretty effect as relieved against the verdant and flowery mead on which they were pitched. To the west of us and just a little to north, stretching away from beyond the base of the Flag-staff Hill, lay a beautiful blue lake.

You may search for it in vain to-day among the mud, scrapiron, broken bottles, and all sorts of red-rusty railway debris—the evidences of an exigeant and remorseless modern civilization. Yet, once, it was there; a real lake, intensely blue, nearly oval, and full of the clearest salt water; but this, by no means deep. Fringed gaily all round by mesembryanthemum (vulgo, ” pigsface “) in full bloom, it seemed in the broad sunshine as though girdled about with a belt of magenta fire. The ground gradually sloping down towards the lake was also empurpled, but patchily, in the same manner, though perhaps not quite so brilliantly, while the whole air was heavy with the mingled odours of the golden myrnong flowers and purple-fringed lilies, or ratafias. I often used (this was in 1841) to visit this lake along with my father on his shooting expeditions, in the early mornings, surprising the numerous wild-fowl that frequented its margin or waded about unconcernedly in its waters.

It was there that, for the first time in my life, I saw snipe killed, and there that I had my first exciting chase on foot after that elusive and noisy bird, the spur-winged plover. Curlews, ibises, and “blue cranes” were there in numbers, and the alert little black-capped sandpipers scuttled along the brink in pairs. Black swans occasionally visited it, as also flocks of wild ducks in passing. In those times, this sheet of water was termed indifferently “The Blue Lake” and “The Salt-water Lake” or “Lagoon”; also I have later heard it styled “Batman’s ” or the ” North Melbourne Swamp.”

Robbed of its ancient surroundings, forsaken by its birds, and pounded into mud by the hoofs of cattle, it came to be called vaguely “The Swamp”, but even so late as 1853, when we came to live for a while in North Melbourne, the winter rains had swelled it again into quite a respectable sheet of water, but the approach to it was as difficult as unpleasant, on account of the mud. Nevertheless, I essayed its navigation in a crank little canvas canoe. The enjoyment, however, I found more than counterbalanced by occasional capsizes and getting out the best way I could through some of the stickiest mud that I can remember anywhere. It was then swamp, and nothing more, yet I could not help thinking that a sail on the old “Blue Lake” would have been something to remember for ever.

Years have passed since the days when it was a swamp even—and now not a single trace of the lake or its former contour remains. It is all dry land now, and I much doubt if many people now living have so much as heard of the “Blue Lake,” which in the “Forties” was one of the chief “beauty-spots” of the northern suburbs. Lower down towards the south and west spread some scattered trees and patches of bushes; behind these again, a dense wall of tea-tree scrub that marked the course of the Yarra, and above which daily curled the smoke from the Governor Arthur, then the only steamer on the river; while, to the southward and eastward of the Blue Lake, gradually rose a pretty green hill of a gravelly formation and known to all the world of Melbourne as the ” Flag-staff Hill.”

Victorian Historical Magazine Vol 2 pp 114-136, 1912, Issue 7. (Read before the Society, 24th November, 1911, and 22nd April, 1912.)

The Early History of North Melbourne.

By Albert Mattingley

I have already mentioned that a large marsh, at first called Batman’s, but which some years afterwards was called the West Melbourne swamp, formed a portion of the western boundary of North Melbourne. It also was the western boundary of West Melbourne, and extended southward nearly to the River Yarra. Between it and the river the land was slightly raised, and on this mound a fine belt of tea-tree grew about 25 feet in height, from which the settlers obtained their clothes-props. Snakes were frequently met with there.

On the waters of the large marsh or swamp lying between North Melbourne and the Saltwater River graceful swans, pelicans, geese, black, brown, and grey ducks, teal, cormorants, waterhens, sea-gulls and other aquatic birds disported themselves; while curlews, spur-winged plover, cranes, snipe, sand-pipers and dottrels either waded in its shallows or ran along its margin; and quail and stone plover, particularly the former, were very plentiful on its higher banks. Many a savoury dish of wild-fowl the sportsmen among the pioneers obtained from this source, the writer among the number. Eels, trout, a small species of perch about 2 inches long, and almost innumerable green frogs inhabited its waters, and the last-named on warm nights held a regular serenade that could be heard over the greater part of the town. At certain high tides this marsh, which covered an area of 75 acres, was subject to tidal influence. It was drained in 1879 by the Government at a cost of £41,373, as it had become insanitary through sewage which had been diverted into it.

Victorian Historical Magazine, Vol 5 pp 80-91 1916 issue 18. (Read before the Society, 29th March, 1915.)

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000  03 9326 9288

03 9326 9288  office@historyvictoria.org.au

office@historyvictoria.org.au  Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm

Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm