This is a series of articles that peel back the layers of history shaping the very ground we walk on, here in the Drill Hall at 239 A’Beckett Street!

Click on the headings below to view the full articles.

1850s: Sands & MacDougall Directories

We begin in the 1850s.

The Sands & MacDougall directory of 1858 unveils a rich mix of businesses along the stretch between Swanston and Elizabeth Streets. Imagine the Merrijig Hotel on Elizabeth Street’s corner, standing alongside Mr. Coglin’s undertakers and Darcy’s Hotel. A tapestry of coachbuilders, blacksmith forges, a bakery, and James Ashton’s sawmill sit alongside solicitors and merchants.

An intriguing detail: the Sands & MacDougall directories of that era spelt the street ‘a’beckett street’, rather than ‘A’Beckett Street’. The 1855 Kearney map below includes the old Melbourne cemetery which occupied the site from 1837 to the early 1850s.

This old Melbourne cemetery is now the site of the current Queen Victoria Market carpark and it is proposed to become an event space called Market Square by the City of Melbourne.

There has always been a government or military building on our block since the Hoddle grid was established. In 1855, the office for the Surveyor and Commissioner of the Crown Lands department was on this block. By 1866, a Drill Hall for the Colonial militia was present and it stayed as a military site until the Federal Department of Defence sold it in the late 1980s.

Image Caption: Kearney Map, 1855

The Radisson Hotel site and the legacy of Samuel Amess

On the current site of the Radisson Hotel, at the corner of William and A’Beckett Streets, once stood a row of double-story terraces known as the Northumberland Terrace. This can be observed in this Charles Nettleton photograph dated 1866.

In the row of terrace houses, the building on the A’Beckett Street corner is wider that the others. It was occupied by business man Samuel Amess who build the Northumberland Terrace.

In the Melbourne Town Hall Reception Room, formerly the old Council Chamber, is a full sized portrait of a bearded male in his Mayoral robes. This is a painting by Tom Roberts, of the Heidelberg School, and his subject is the Mayor (1869-1870), Samuel Amess.

Amess was born in Fife, Scotland in 1825, started work as a stone mason before coming to Victoria to seek his fortune. He established a successful building business and was responsible for constructing notable landmarks, including the Treasury, the ‘Old Exchange,’ the Customs House, the Kew Lunatic Asylum, and the Government Printing Office.

He was also known for his generosity. When the current town hall was opened Amess had a celebration for 20,000 people, most of the cost paid for out of his own pocket. He was also a member of the West Melbourne Bowling Club and West Melbourne Presbyterian Church.

The Sands & MacDougall directory also indicates that Amess owned timber yards on William Street. There were a number of timber and storage yards in the vicinity. The 1895 MMBW maps for the area demonstrates how many there were. These businesses continued to operate on A’Beckett Street between Queen and Elizabeth Streets through the turn of the century.

You may also notice in the photograph, that the West Melbourne Orderly Room, utilised by the Colonial Volunteer forces, was situated across A’Beckett Street from the terraces. This site is where the RHSV Drill Hall is now located.

In the 1960s the sites on William and Franklin Streets were the home to the Bearing Service Co. of Australian P/L and Containers Ltd. The Franklin Street corner then became the site of Melbourne City Mazda.

In 1977 Victoria Police headquarters moved to a multi-storey office building on the terrace site, 380 William Street and the building was later refurbished to become the Radisson Hotel.

Chris Manchee

Image Caption: Charles Nettleton, 1866

1860s: The Explosive History of the A’Beckett Street Flock Factory

First, what is a flock factory? Flock and flocking are still used today but were more common in the 19th century. It involved processing rags into small pieces for various uses. Larger, coarser flock could be used as mattress filling, while the finest flock could be used to create a raised velvety feature on wallpaper. In 1865, Messrs. Eastwood Brothers and Co.’s flock Manufactory on A’ Beckett Street was situated between the now-defunct Coglin Place and Stuart Street, just over Elizabeth Street towards Charles Swanston Street. By the mid-1860s, this area was a mix of light industry, businesses, and poorer residential usage. Newspapers of the time described it as the most densely populated section of Elizabeth Street. It was in the midst of this mix that the great flock factory explosion occurred.

Accounts of the incident vary, but there are many points of agreement. It appears that everything was normal on Monday, June 5, 1865, until around 7.45 in the morning when a tremendous crash signaled the explosion of the boiler: “The end of the boiler was blown completely out, and the huge iron mass, measuring 18 feet (5.5 m) in length, was shot from its position like a tremendous conical shaft from a gun. It passed completely through the portion of the factory used as a store, destroying a flock-cleaning machine, which was reduced to atoms. It made its way with tremendous force through a brick wall and eventually landed on the opposite side of the street, having traveled a distance of 40 yards (36.6 m), with the edge of the boiler coming to rest against the curbstone. If this had not happened, the entire mass would have ended up in the neighboring premises.” [Source: Melbourne Herald, reproduced in the Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser, p. 4, Monday, June 5, 1865]

Frederick Eastwood, the engineer who was near the boiler when it exploded, was badly scalded and later died. Miraculously, he was the only official fatality given the force of the explosion. As an example, a brick smashed through the window of the Times Tavern on Elizabeth Street. The steam box, which was previously attached to the boiler and weighed between 400 and 450 kg, hurtled through the air and landed just meters from where a man and a boy were working. “A plank 12 feet (3.6 m) long was driven into the bedroom of an adjoining dwelling and fell onto the bed, startling a woman and child from their sleep due to the explosion’s noise” [Source: Australian News for Home Readers, Saturday, June 24, 1865, p. 11].

Mr. Frederick Dalgetty was hit on the head by a falling brick but eventually recovered. It was undoubtedly a terrible catastrophe, but it could have been much worse.

|

|

|

| Image Caption: The Leader, Sat 3 June 1865 |

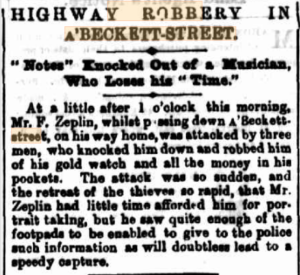

1870s: Tales of Intrigue and Lawlessness: A’Beckett Street’s Dark Past

While A’Beckett Street today is considered one of the more peaceful parts of the city, this has not always been the case. In the late 19th century, A’Beckett Street was a much more perilous place, plagued by violence and robbery.

As early as January 1873, The Herald reported a case of “HIGHWAY ROBBERY IN A’BECKETT STREET.” The report stated, “At a little after 1 o’clock this morning, Mr. F. Zeplin, while passing down A’Beckett Street on his way home, was attacked by three men. They knocked him down and robbed him of his gold watch and all the money in his pockets. The attack was so sudden, and the thieves’ retreat so rapid, that Mr. Zeplin had little time to provide a description. However, he saw enough of the footpads to give the police information that would likely lead to a speedy capture.”

By the 1880s and 1890s, there were reports of muggings where unsuspecting men befriended thugs in a pub. Then, in the company of their new acquaintances, they were lured into A’Beckett Street or the surrounding lanes, only to be summarily attacked or “garroted” and relieved of their cash and belongings. Robberies targeted both property and individuals.

In July 1891, Messrs. Moss White and Co., tobacco manufacturers on the corner of Wills and A’Beckett Streets, were robbed of £450 worth of tobacco goods. The getaway vehicle, a horse and cart, was later found abandoned in Clifton Hill.

An attempted robbery at the Fire Brigade Hotel in the east end of A’Beckett Street in 1887 demonstrated considerable sophistication. A group of men entered the hotel late one evening, ordered drinks, and then attempted to pay with a £10 note. This required the publican to get change for such a large amount. As she went upstairs to access the cashbox, another member of the gang was stationed in the street opposite. By following the progress of her candle, he was able to determine where the cash was kept. While the group inside the hotel continued playing cards, suspicions were aroused. The publican went back upstairs just in time to catch a man escaping through the back window. He was chased across rooftops and through lanes by a hotel patron and was eventually caught with £61 18s taken from the Fire Brigade Hotel’s cashbox.

The final story from 19th-century A’Beckett Street is not a crime but provides insight into the conditions at the time. An employee of Cameron’s Tobacco Factory in A’Beckett Street, near The Oxford Hotel, named Donald was unknowingly left behind in the premises one Thursday evening. He died of natural causes and was discovered on Friday morning when the upper room was opened. An army of rats was found gnawing at the deceased body (Source : Goulburn Evening Penny Post, Saturday, December 2, 1803).

Sabloniere Hotel, Corner of A’Beckett and Queen Streets

The southwest corner of Queen and A’Beckett Streets is currently home to yet another generic office building with ground floor retail, but it used to be the home of the more colourful Sabloniere Hotel.

The new Sabloniere was built by Charles Rupprecht in 1865. It was named after an earlier hotel of the same name that he’d owned further south in Queen Street.

The new Sabloniere was described as an establishment ‘which will be found replete with everything conducive to comfort and convenience.’

This hotel seems to be a step up for Mr. Rupprecht and the Sabloniere as just eight years earlier the license application barely squeaked through when ‘The Bench granted the license application observing that the license of the house was refused on a former occasion on account of the character of the applicant. On the present occasion the license was granted, the applicant being advised to conduct the house in a respectable manner.’ (The Argus 9 December 1857, p.6)

Both the new Sabloniere and Mr. Rupprecht seem to have benefited from this advice. The hotel soon established itself in the area, which was rather different and more industrialised than the one we think of today. Within a short distance of the newly opened hotel was Thomas Holton Tea & Sugar Sorter and W. Roberts Reaping & Threshing Machine Maker, as well as the West Melbourne Orderly Room on the corner of William Street.

The Sabloniere contributed to the social life of the area as its site included a bowling green for both guests and the general public. This bowling green led to the formation of The West Melbourne Bowling club on the 18th of August 1866: ‘At the request of several gentlemen who are desirous of having the Bowling Green of the Sabloniere Hotel, Queen Street, reserved for their exclusive use on certain days each week the Proprietor has resolved on Establishing the above named Club’, (City of Melbourne Bowls Club History).

The bowling club, now the City of Melbourne Bowls Club, remained at the site until 1972 when it relocated to the nearby Flagstaff Gardens.

The Sabloniere was distinguished not only by its bowling green but by its name. It seems likely it was named after The Sabloniere Hotel in Leicester Square which was apparently popular with Italian visitors to London. Perhaps Charles Rupprecht was seeking to draw on this as he advertised that ‘French, German and Italian was spoken at his hotel’ (Peter Andrew Barrett – Architectural and Urban Historian, Writer & Curator Facebook 10 June 2021). Whatever the reasons, under Mr. Rupprecht’s management the Sabloniere flourished and in 1875 additions were made to the hotel including a new dining room and several more bedrooms.

When Charles Rupprecht died in 1878 he must have left a sizeable estate as he bequeathed £1,700 to the Melbourne Benevolent Society and similar amounts to the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum, the Melbourne and Alfred Hospitals, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, St. Francis Church and St. Mary’s Church.

The Sabloniere continued long after its founder, finally closing its doors in 1972.

Image Caption: Isometrical plan of Melbourne & Suburbs, 1866

By long term RHSV Volunteer Julie Bevan.

Healings Radio :115-125 A’Beckett Street

The stylish Art Deco building at 115-125 A’Beckett Street currently houses Uno Melbourne Apartments. However, it was originally built as the ‘works’ for Healings, a company headquartered around the corner at 167-173 Franklin Street.

Alf Healing, born in Richmond on August 23rd, 1868, and died in Kew on February 18th, 1945. Kew, only a short distance across the river from Richmond, was, in those days, like the other side of the world. The Yarra River served as a significant boundary, akin to a city wall, dividing the haves from the have nots. Alf Healing’s journey from obscurity to wealth is written in his addresses.

Initially, Alf’s success in business can be attributed as much to good fortune as to good management. He was working as a not too successful real estate agent in Bridge Road where his path to the top was hampered by his own generous nature – he was known to pay rents out of his own pocket – and the tendency of locals to do ‘moonlight flits’, when an opportunity came his way. Some local mates wanted to club together to import bicycles from the U.K. as they were expensive to buy locally but they needed one more member for their group so Alf Healing joined and became negotiator for the syndicate in their dealings with Haddon Cycles. They imported 50 cycles at a cost of £10 each and sold them for £16.10 when the going price in Melbourne was £30. Unfortunately, for the aspiring bicycle tycoons, the first shipment arrived with chipped enamel and without the Haddon label. Initiative and hard work combined to guarantee success, and by 1898 he had his own small bike sales and repair shop in Richmond.

His move from retail to wholesale was again more by accident than design as a much larger consignment of cotter pins than expected was delivered as someone had failed to notice the word ‘ditto’ on the order form and twelve times the intended amount arrived. Undeterred Alf packed the excess into paniers, cycled to Ballarat and sold the lot. Thus inspired Healing Cycles expanded into the wholesale business and manufacturing.

Under Alf Healing’s astute management, the business expanded, relocating to larger premises in Niagara Lane in the city, then to Post Office Place in Carlton, and ultimately to a large purpose-built factory at 167-173 Franklin Street in 1929. The ‘works’ in A’Beckett Street opened in 1937.

Over time, A.G. Healing Ltd. diversified into manufacturing and selling electrical goods, with a focus on Healing’s ‘Golden Voiced’ Australian-made radios (1933). The business flourished and diversified far beyond the initial aspirations of the small bicycle shop becoming one of the largest companies in the southern hemisphere with branches throughout Australia and New Zealand. It continued after Alf’s death as an electrical manufacturer producing televisions, refrigerators, washing machines and stereograms. It lasted until 1975 though the ‘works’ had long since transferred to Preston.

By long term RHSV Volunteer Julie Bevan.

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000

239 A'Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria, 3000  03 9326 9288

03 9326 9288  office@historyvictoria.org.au

office@historyvictoria.org.au  Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm

Office & Library: Weekdays 9am-5pm